In A Story Made of Pasta, Franco Sessa returns to his hometown of Gragnano, Italy, to explore the rich history of pasta making and the people keeping its traditions alive today.

The arrival area of an international airport is always the gateway for great adventures, whatever it is for a well-deserved holiday or a family reunion or just conducting business. If these reasons together have you landed at the Naples-Capodichino International Airport (Italy), then you know you are in for a memorable time. Bright digital billboards are strategically located along the custom and the duty-free areas to capture the attention of the tourist and influence their spending whereabouts. Breathtaking photos of the Faraglioni rocks in the island of Capri, the Veiled Christ sculpture in the Sansevero Chapel, the picturesque cliffs of the Amalfi coast paraded along a corridor and one poster stood out. No pictures just words in bold characters “Italians consume 23kg of pasta per annum pro capita, Italians eat pasta on average 4-5 times a week, one Italian out of two choses pasta as their preferred food”. The sight of these words resonated as an omen to me, somehow some marketing agency managed to read my mind and discover the reason of my trip; learn more about the history of the pasta. The location of my research? The town of Gragnano, known as the Italian capital of the pasta or the City of Pasta. I knew my way, very well, familiar locations with many happy memories from growing there as a child, the hometown of my parents, now their chosen location to live their retirement years.

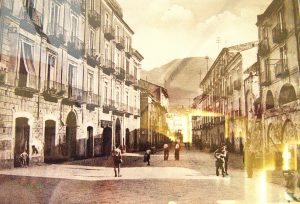

- Murals welcoming visitors to Gragnano the Capital town of Pasta

Driving from Naples on the southern motorway toward the city of Salerno, the offramp sign “Sorrento-Positano-Amalfi “reveals a dramatic landscape in the background, made of coastline on the right and dark green mountain on the left. Those mountains are the backbone of the popular rock cliffs that have made the Amalfi coast so iconic and desirable. The same mountains and their valleys also nurture the foundation and existence of laborious small towns, like Gragnano. It was in the early 1800s that Gragnano became first world producers of pasta, stapple food to feed the kingdom of southern Italy with its 9 million of inhabitants (the most populated state in Europe at the time), other European states and the Northen states of America with their massive flows of European immigrants. More than 100 pasta making factories in Gragnano were an integral part of a large-scale agricultural revolution, where local and imported grains were converted into the added valued pasta, a product not only great to feed and nourish the masses but also contributing to great revenues for the kingdom and its foreign trades. The pasta making industry was such a phenomenon that the King Francesco II of Borbone itself, declared the official title of “Maccheronaro” to the artisan pasta makers who curated the art of making “Maccheroni” (pronounced mah-keh-ROH-nee), a short tubular type of pasta. Maccheroni became so popular in the American subcultures that the traditional word maccheroni soon assumed a lazy pronunciation and rolled out from the tongue as “macaroni”.

Saying the word “macaroni” or ordering a cappuccino after 11 am while visiting Italy is a total blasphemy toward the local food identity!

Today, of those hundreds of pasta factories, only a dozen remain. After decades of geopolitical wars, agricultural setbacks and evolution of global nutrition trends, the historical “maccheronari” struggle to preserve the precious art of traditional pasta making against corporate giants. The family business Pasta Cuomo hold the fort with their small artisan factory still located in the heart of Gragnano, along the street called Via Roma (Street of the Pasta Makers). Their name is well documented in the archives of the Kingdom for their immense contribution to the industry and, apparently, the King ‘s favourite brand! Seven generations of dedicated craftsmen (and women) which stood out from the rest for their innovation and vision; the process of bronze drawn (extrusion) and drying with natural occurring air flow (sea breeze), made their pasta unique and of the highest quality. The reins of the family business are now in the hands of Amelia and Alfonzo. Their challenge is to connect the family trade with the high-end restaurants worldwide with their limited batches of handmade pasta. Only two ingredients: water and flour! When I asked where the two ingredients were historically sourced, Amelia pointed the finger out of the factory window and said “One kilometre walk up the hill that way!”

Old derelict watermill, a statement of a rich history of terroir and traditions.

A short walk later, negotiating the uneven basalt surface of the main road, we stood by a tourist sign saying “Benvenuti nella Valle dei Mulini” – “Welcome to the Valley of the Watermills”. The sound of the Vernotico stream draws our attention to its path, a narrow and steep gorge geologically dug within two green mountains over the course of thousands of years. It was here that around the XIII, dozens of watermills were built on the ridges of the gorge to capture the endless mechanical energy provided by the stream. Horizontal waterwheels powered grinding stones capable of milling large volumes of grains into flour and satisfy the growing demand of the pasta makers in the village downstream. This futuristic and environmentally friendly displacement of watermills was probably one of the first industrial complex of the Old World, the same water that powered the watermills was also utilised as an ingredient in the pasta making process, all forces and resources offered by nature and cleverly harnessed by the local villagers. With the end of the kingdom and the annexin to the Republic, the strong local economy subsided and moved elsewhere, the whole valley of the watermills fell into a state of abandon and almost lost in time with the stone ruins completely overcame by vegetation. In recent years a local resident, Mr Pietro Ingenito, has challenged and lobbied local authorities to bring the Valley of Watermills back to life and regain its terroir status. Leading a handful of fit and enthusiastic volunteers, Mr Ingenito works relentlessly to restore the watermill buildings, clear the vegetation, and promote this fantastic and unique archeologic industrial park by providing guided tours to tourists and locals. Public awareness and educations are often the best tools to reach distracted local administrations and unlocked meagre funds for professional restoration projects. While visiting this open-air museum, my imagination re-enacted the work of hard-working men and women, milling flour day in and day out, then transporting their daily production a few kilometres down the road where pasta makers were ready to convert it in that culinary miracle nowadays enjoyed worldwide.

The conclusion of our visit and journey ended with a short stroll to my parent’s place, where my mama prepared for lunch, a traditional pasta dish, “pasta e fagioli “(pasta with beans), a meal indeed fit for a king with lots of fond memories. We all agreed that that dish of humble origin has somehow preserved a tale of traditions and human history, a story made of Pasta!

Franco Sessa, known as The Grand Gourmand, is an international cheese judge and owner of Grand Gourmand. Based in Auckland, Franco judges at both the World Cheese Awards and New Zealand Champions of Cheese Awards. He also hosts cheese and wine pairing masterclasses and contributes seasonal gardening and sustainability columns to MiNDFOOD magazine as Gardening Editor.